Analyzing the Arguments For and Against Preemption in APRA

[Updated 5/8/2024: 15 State Attorney Generals sent a letter to Congress stating “Federal Data Privacy Law Should Set a Floor, Not a Ceiling.”]

One of the core purposes behind the proposed American Privacy Rights Act (APRA) is to “eliminate the patchwork of state laws” by having a “uniform national privacy” standard in the United States. It does this via preemption of State privacy laws. Section 20 (a)(1) of the current draft of APRA “expressly preempt laws of a State or political subdivision thereof” to “adopt, maintain, enforce, or continue in effect any law, regulation, rule, or requirement covered by the provisions of this Act.” APRA also preempts other federal entities (such as the FCC) of “its authority to police potential privacy abuses.” The APRA puts all the rulemaking eggs for privacy in the US in the FTC’s basket, with enforcement by the FTC and State AGs as well as a private right of action.

Given that APRA would effectively kill approximately 17 comprehensive State privacy laws and a host of other State privacy-related laws, such as the California Delete Act, I thought analyzing the arguments for and against preemption would be a good exercise. To be upfront, I personally believe we should have a strong national privacy law that still lets States innovate and respond to the rapid pace of technology to protect their residents and has a high floor so that it would be a rare occurrence for a State to go beyond the floor. At the end of this blog post, I also provide a proposal that tries to bridge the preemption divide.

Arguments *Against* Preemption in APRA

#1 The Slow Pace of Updating Federal Privacy Laws.

Privacy law at the federal level moves at a glacial speed, so if we have APRA’s ceiling, I fear we won’t be able to keep up with rapid changes in technology (e.g., AI). As Professor Daniel Solove previously noted in the prior Federal privacy debate:

Congress is notoriously bad at updating laws. If Congress were a landlord, it would be a slumlord, because Congress hardly ever updates privacy laws even when they scream for an update. The Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) is closing in on being 40 years old. It was passed in 1986. If you were alive back in 1986, recall email, computers and the Internet back then. This was the digital stone age. Despite urging from all sides (law enforcement and privacy advocates) to update ECPA, has Congress done anything? Nope. There have been countless bills that have suffered the same fate as the ark in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) has a similar story. It’s woefully out of date and has countless shortcomings. It’s about 50 years old. I guess that’s young when so many people in Congress are in their late 70s, but for a privacy law, it is long overdue for an overhaul. As with ECPA, there have been bills, so many bills, but most bills wither on the vine.

Take the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) which bans collecting data from children under thirteen without parental consent. It was passed in 1998. This is pre-iPhone and pre-social media. We are still waiting for COPPA version 2, and the current proposal for V2 has it covering teens up to sixteen and an outright ban on behavioral advertising for those under sixteen. Ironically, an editorial in support of APRA highlighted COPPA and said this

And APRA can be strengthened over time. That happened with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act, passed in 1998 to protect children under age 13. In 2013, the law was broadened and updated by the Federal Trade Commission to reflect evolving technology such as mobile devices.

The fact that it took 15 years for the FTC to broaden the law (and not upgrade it like COPPA 2) is not a good endorsement of how privacy law is done at the federal level, so I am not sure we want to put privacy policy in amber given the rapid technology innovation that is occurring.

#2 You Lose the Power of State Innovation.

As noted by Justice Brandeis:

it is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.

Thus, with APRA, we will lose the ability for States like California to be the agile laboratories of Democracy when it comes to consumer privacy. I am concerned that shutting down this laboratory of innovation when it comes to consumer protection in the new world of AI is not a good thing to do. And doing so when national privacy laws move at a glacial speed exasperates things further.

APRA also breaks historical precedent in this regard. As noted by the California Privacy Protection Agency:

Traditionally, federal privacy legislation has set a baseline and allowed states to develop stronger protections. For example, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), and the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), among others, include language that enables states to adopt stronger protection. California has often done so. The Confidentiality of Medical Information Act and the California Financial Information Privacy Act are just two examples of California laws that build on the federal baseline. This approach has not prevented California from becoming one of the largest economies in the world.

What does a laboratory of Democracy look like? A great example is California, which is open and agile in keeping up with technology. As Justin Brookman with Consumers Reports noted, “California alone iterates and advances on its own privacy legislation every year.” IAPP even tracks all California legislation, and they are tracking 31 privacy and AI-related bills in 2024 alone. For example, SB 1223 would amend the CCPA to define “sensitive personal information” to include a consumer’s neural data. Or take AB 2877, which would amend the CCPA to prohibit a developer from using the personal information of a consumer under 16 to train an artificial intelligence system without affirmative authorization. In fact, over the last two legislative sessions, we have seen major innovations such as the Age Appropriate Design Code and the California Delete Act. The point is in a State like California (and now also Colorado), privacy laws are enhanced in a timely manner, unlike what we see at the federal level (e.g., COPPA, which has not been updated since 1998 even though we have gone through revolutions in mobile, social media, and AI).

Finally, say you are an environmentalist, are you not glad that California can set auto-emission standards, as this has historically set the bar for the auto industry and been a net positive for the environment? I think the same analogy can apply to privacy.

#3 Significant Privacy Rights that Exist Today will be Lost with APRA Preemption.

APRA’s preemption will cause States and their citizens to lose privacy rights that go beyond the current baseline that APRA has. For example, with the California Delete Act, starting in 2026, Californians can initiate a deletion request to hundreds of data brokers in a single action. The APRA alternative of manually contacting hundreds of data brokers and then repeating that exhaustive process a few months later is impractical to the point of being impossible for the average consumer. Thus, in the case of the California Delete Act and Californian’s 40 million residents, APRA and its preemption will represent the second-greatest loss of a privacy right in United States history (the greatest and most significant being the Dobbs decision).

Another example is that, per the CPPA, APRA “also lacks critical protections with respect to sexual orientation, union membership, and immigration status” that exist in current State laws that include these categories in the definition of sensitive covered data.

Fifteen State Attorney Generals also noted that APRA will delay some consumers’ privacy rights that they enjoy today. For example,

Many Americans are (or will soon be) enjoying their existing privacy rights and businesses have developed mechanisms to respond to consumers exercising their rights, including online user-enabled global opt-out mechanisms, like the Global Privacy Control. As the APRA is currently drafted, Americans will have to wait an additional two years to exercise their privacy rights via the Global Privacy Control until rulemaking is completed.

The point is that preemption not only impacts any future ability for a State to add privacy rights but pushes out or kills any State’s current privacy rights that go beyond the current APRA ceiling. In a post-abortion rights America, should we be clawing back hard-fought rights that are already in place?

#4 Preemption FACILITATES a Chokepoint for Industry Lobbyists to Block Privacy Laws.

We have seen the massive amounts of lobbying by large tech firms in DC to historically bottle up progress on privacy, antitrust, and other matters, while the same lobbying groups have, in many cases, lost comparable battles at the State level. A case in point is … the California Delete Act, which was able to pass despite fierce lobbying by tech groups, while the comparable federal DELETE Act has not progressed. Another example is the recent passage of the Maryland Kids Code (hopefully to be signed soon by the Governor), while the federal Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) still lingers. So, preemption makes it far easier for the big-spending lobbyists to concentrate their efforts on a dysfunctional Washington DC to gum up the works and centrally choke policy innovation that protects consumers.

#5 Project 2025.

For this one, I am going to talk politics, as you can’t divorce politics from policy. This argument is probably best for the ears of people who are or lean Democratic. So, feel free to skip this one if you think I am getting too political.

I think we can all agree that Donald Trump probably has a 45 to 50% chance of winning in November 2024. If he wins, he is committed to deconstructing the administrative state, and the Heritage Foundation is leading a project called Project 2025 to implement that on his behalf. As noted by Meredith Whittaker, the CEO of Signal, this project is a:

a coalition led by the Heritage Foundation and shaped by former Trump personnel that is focused on assembling an army of 20,000 potential administration staffers “to begin dismantling the administrative state from Day 1” and to centralize power under the executive branch such that it could unilaterally enact policies, including a federal abortion ban. This dovetails with the Trump campaign’s own stated plans, which focus on casting off as many checks on presidential authority as possible and bringing “independent agencies — like the Federal Communications Commission, which makes and enforces rules for television and internet companies, and the Federal Trade Commission, which enforces various antitrust and other consumer protection rules against businesses — under direct presidential control.”

So, what is Project 2025’s philosophy with respect to the FTC besides nuking its independence? Well, let's read their plan for the FTC, which includes this quote:

Conservative approaches to antitrust and consumer protection continue to trust markets, not government, to give people what they want ...

Combined with Project 2025’s personnel database of 20,000 people dedicated to deconstructing the administrative state, this basically means they will want to staff the FTC with people from industry (i.e., “the market”). Don’t believe me that a bureaucracy would be transmogrified to support industry under a new Trump Administration? Then you must not be aware of what Mick Mulvaney tried to do to the CFPB under the last one — a “Master Class in Destroying a Bureaucracy From Within” — or how Trump appointed an ex-coal lobbyist to run the EPA. Or, at the very least, these groups will lean on Trump not to enforce privacy violations in their industry, and he has been known to flip-flop based on what his donors want (e.g., TikTok).

And we certainly know that Trump and his followers are selective in how they view the right to privacy. For example, see the Dobbs decision that overturned Roe v. Wade — which was “a ruling grounded in the right to privacy” — and also this:

Indiana’s attorney general has argued that abortion records should be publicly available, like death records; Kansas recently passed a law that would require abortion providers to collect details about the personal lives of their patients and make that information available to the government. Birth control and sex itself may be up next for criminal surveillance: the Heritage Foundation, last year, insisted, on Twitter, that “conservatives have to lead the way in restoring sex to its true purpose, & ending recreational sex & senseless use of birth control pills.”

Please note that the Heritage Foundation was the first featured quote in the Senate Committee’s press release regarding supporters of APRA. Other organizations expressing their support in that press release include industry groups that represent large tech firms.

Sorry to interject politics into this discussion, but if you are a Democratic representative in Congress, you may not want to unilaterally disarm and preempt States and the FCC when it comes to privacy before you know the results of the 2024 election. If you are upset about me bringing this up, please note that I just quoted Project 2025’s plans, and I take them at their word that they will implement that plan.

Arguments *For* Preemption in APRA

#1 APRA Exceeds All Current State Laws, So Perfectly OK that APRA has Preemption.

When APRA was announced, its co-author says is “stronger than any state law on the books.” The argument then is if it is better than every State law, it is OK to have the preemption in it, because it is a moot point that States would or could exceed it.

The counterargument is that APRA in its current form is, in fact, not better than various State laws in key areas. This is not me talking; see comments by Rep. Pallone and Rep. Trahan. So, the “stronger” argument is not representative of what is actually in the books, and therefore if an argument is predicated on something that is not true, then the argument is invalid. One could plausibly argue that if a supporter truly thinks APRA is the best across the board, those supporters should not be afraid to remove preemption from it.

#2 Either APRA is “Last” or “Best Chance” for a Federal Privacy Law, So We Should Just Accept the Deal that Includes Preemption.

This is the “Last Chance Saloon” argument. It’s closing time, so you had better drink up because we will never be able to pass the national privacy law again.

The counterargument is this is a false sense of urgency because we heard this exact argument with ADPPA in 2022:

Representative Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA), the Republican leader of the Energy and Commerce Committee, said in a statement that 80 percent of Americans reportedly support the priorities in the ADPPA.

"As I said before, this is the best chance we have ever had to achieve a strong national standard that protects Americans, no matter where they are or if they travel across state lines.”

#3 We Should Accept Preemption So Citizens Of States without a Privacy Law Can Get Privacy Rights.

Right now, nearly 20 States have a comprehensive privacy law that affords their citizens digital privacy rights—with the addition of 10 or so in the last year with many more in the pipeline—so yes, it would be great if everyone in the US had privacy rights. In fact, per eMarketer, nearly 2/3 of States either have a privacy law or have a current proposal for one:

But … the counterargument is that you don’t have to have preemption in a national privacy law to make that happen.

And I understand that supporters of APRA in its current form may respond, “But that’s the deal on the table, and this is realpolitik, and that’s the trade-off.” My response is that the current trajectory has us adding about 10 State privacy laws per year, so there is a good chance the vast majority of Americans will have reasonable consumer privacy rights in 2-3 years anyway, and we will get there without locking ourselves in amber into a deal that does not let us easily upgrade our privacy laws for decades. So, we don’t have to rush into a deal with a false sense of urgency because time is on our side, and in relatively short order, most States will grant their citizens privacy rights.

I am also not a fan of this argument that XYZ state has to trade away its hard-won privacy (e.g. the right to delete en masse from data brokers) so another State can have basic privacy rights. In other words, if you believe privacy is an inalienable human right, and given that “inalienable” right means something that can’t be sold or bartered or traded away, then what’s up with the willingness to get into a Faustian bargain to make a deal to have one State lose some its privacy rights for another State to gain theirs?

#4 Preemption makes it Easier for Businesses Because it Eliminates the Existing Patchwork of State Comprehensive Data Privacy Laws.

As noted by R Street:

The number of states passing their own privacy laws continues to increase, creating a patchwork of state privacy laws, each with their own compliance, red tape, and associated costs.

That’s a valid point, as more State laws represent more complexity for businesses to adhere to them.

[Although ironically, most businesses are perfectly fine with the patchwork of relatively weak State data breach laws and have not pushed for a strong federal data breach standard, so it is not like they are always consistent in their demands for a national standard when it comes to privacy or cybersecurity. They tend to favor whatever is in their best interests, so if having a patchwork of weak State laws is in their interest versus a strong national law, so be it.]

So here is how this patchwork looks to businesses:

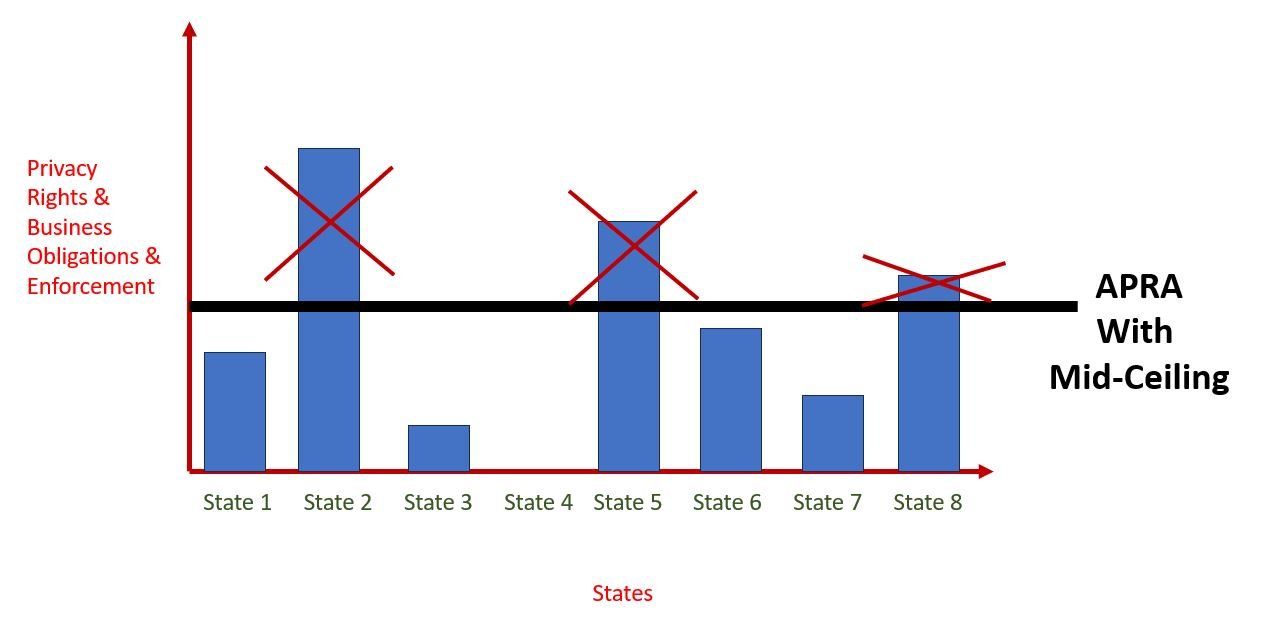

Below is the picture with APRA, with a consistent set of rights and obligations and enforcement below the black line. Yes, it gives many States better privacy and makes it easier for businesses to deal with a single standard, but it eliminates existing privacy rights from some States and locks us into this ceiling with little chance to move it up in a timely manner. And yes, businesses would love this (especially the Big Tech companies who don’t want to deal with California or other States coming out with regulations that put some guardrails on them, and their lobbyists will be able to effectively bottle things up in DC), but it is not good for consumers in the long run and very bad in the short run for consumers in States that right now have privacy rights that exceed the proposed APRA ceiling.

My counterargument is, let's actually do what the co-authors said they would do, which is really make the law stronger than any state law on the books but also make it a floor versus a ceiling. This benefits consumers, and the reality is that maybe one or two States may exceed the floor, so this is not a patchwork that businesses are dealing with but a few isolated areas. Here is what I am counter-proposing:

We actually have that today for other privacy-related laws. HIPAA and FCRA are both privacy laws that set a floor, not a ceiling, and the sky hasn’t fallen. No one is writing editorials that say it is “nutty” that California’s Confidentiality of Medical Information Act (CIMA) extends HIPAA. History shows that most States will stick with the federal baseline, and a few will push further.

But a preemption fan may still say something like this when it comes to having States exceed the federal baseline:

[this] play[s] right into the hands of the biggest companies, that can afford to craft different policies for different states, or that can figure out ways to craft policies that comply with every state. But it would be deathly for many smaller companies.

My response is that, again, history has shown that an overwhelming number of States stick with the federal baseline, so this is a red herring. And note that APRA has already set a high exemption bar for companies that fall under APRA—$40 million in revenue (which is higher than California’s law, which sets the exemption bar at $25 million). In fact, the US Census defines a “small business” as a company under $40 million, so all small businesses are exempt from APRA.

One compromise is that you could also put into a national privacy law that for any State laws that go beyond the floor, the exemption bar for that State law would be raised to, say, $60 million of annual revenue, for say 2 years, to give smaller businesses time to adjust before the State-specific step-up.

This means under this idea that this patchwork issue is minimal, can only apply to the largest entities, and consumers are not screwed in the short and long run. So, if we get a bit creative here, we don’t have to be forced to have all these trade-offs that APRA forces on us with preemption.

Final Thoughts

I know some readers may be saying, “Well, he’s from California and worked on some California laws, so he is biased.” I should point out that all my critiques of the lack of features in APRA have been echoed by non-Californian politicians, and my critique of preemption overlaps with what 15 State Attorney Generals have said, as well as many privacy groups such as Consumer Reports, EPIC, EFF, etc. (e.g., here and here). And to be clear, I do want a national privacy law, and I appreciate the work put into this effort. But I just think it is very bad for consumers to require preemption to get this deal done, and instead of solely complaining about preemption, I have at least tried to put forth a compromise proposal (and not saying it is good, but we need to find ways to bridge the gap).